See? Hacking is a mindset, not a skillset. When you seek, in your everyday life, to deliberately find opportunities to be clever, ethical, to enjoy what you are doing, to seek excellence, then you’re hacking. They translate this clever, ethical, enjoyable, excellence-seeking behaviour to their everyday lives. We can tinker, re-design, and play with them.” It went on to say that participants in Silicon Valley companies “don’t ask for permission to do what they do… They are less interested in technologies per se than in playing with established ways of doing things and conventional ways of thinking, creating, learning, and being.” A recent Harvard Business Review blog post described Silicon Valley as having a culture that believes “things are hack-able- that the way we’ve designed various systems is not pre-ordained or immutable. But the principles of creativity and cleverness are still there, although the fun may be more intrinsic than obvious to us the outside observer.

Now within the mainstream, the term hacking has been appropriated to describe people who hold these same values and do computer programming. What have you done today that can be said to have “Hack Value”?

Activities of playful cleverness can be said to have “hack value.” Hack value. The list of hacks includes lining a hall with invading green army men, installing a lunar module on top of the Great Dome, setting up a giant statue of Athena on a main lawn, and my personal fave, hanging mannequins on high wires and trapezes from a ceiling along with long flowing ribbons, to turn a lobby into a circus.Īlong these lines, I found a fantastic quote in the Wikipedia definition of “hacker”: “Hacking entails some form of excellence, for example exploring the limits of what is possible, thereby doing something exciting and meaningful.

The website (there’s always a website) dedicated to cataloguing the pranks is actually called the Hack Gallery ( ). When the MIT hackers hack, their goal is to devise “a clever, benign, and ‘ethical’ prank or practical joke, which is both challenging for the perpetrators and amusing to the MIT community.” The MIT hackers describe what we call “hacking” as “cracking”. You see, originally, hacking had nothing to do with computer programming: In fact, “hack” was originally a term used to describe pranks performed by MIT students: their pranks are projects or products that are completed to some end, but that also afford the participants some enjoyment by the mere fact of participating. And I don’t mean by sitting at a computer every day I mean by hacking in the true sense of the word.

#Game hacker one key modification software#

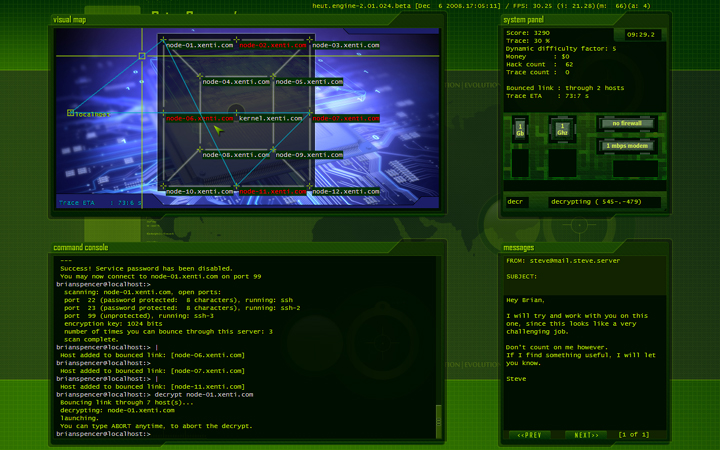

When I say “hacker” what images come to mind? Some pimply-faced kid in a dark basement, breaking into a high security website to post a picture of a LOL cat? Or a hoodied twenty something male typing furiously with his Guy Fawkes mask beside him, liberating corporate, government or military documents in the name of Anonymous? Using AutoCad software of course, as the movies would have us believe.īut how many of you have referred to yourselves as a hacker? You probably should. My goal is to either convince you that you’ve been hacking all along or that you really should be hacking. But why hacking? Much like gamification is the application of game design principles to non-game uses, the principles of hacking can be applied to non-hacking uses. Tanya Snook makes the case for everyday hacking and provides five principles that you can use to rethink situations, re-evaluate problems, and hack everything you do. From MIT’s famed pranks to Silicon Valley’s approach to design, core values drive the clever, ethical, enjoyable, excellence-seeking behaviour of a civic-oriented hackers mindset.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)